Quantifying a Greener Future for Freight

Freight Research • Published on October 10, 2019

This post was originally published on Convoy’s Tech Blog on Medium

There is a dirty secret in the freight industry.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), medium- and heavy-duty truck freight accounts for 7 percent of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, or 436.5 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2017 (the most recent year of data available at the time of this writing). An estimated 76 million metric tons of those occur while trucks are running empty.

By most estimates, about one-third of the miles driven by heavy duty trucks with dry van or refrigerated trailers are run empty — a number that has proven stubbornly intractable in recent decades. It does not have to be this way.

Environmental sustainability is core to Convoy’s mission of transporting the world with endless capacity and zero waste. Our recent innovations to group shipments together so that truckers can run more efficient routes demonstrate a more environmentally sustainable path forward for the freight industry. We conservatively estimate that there is the potential to reduce the carbon emissions associated with trucks running empty by 45 percent, or 34 million metric tons — comparable to the total annual carbon emissions of Oregon.

Freight industry carbon emissions

The EPA estimates that U.S. medium- and heavy-duty truck freight emitted 436.5 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2017, the most recent year of data available at the time of this writing. But the scope of waste is not necessarily comparable across different segments of the freight industry. Consider two common types of trucking services:

- Full truckload (FTL): The transportation of bulk goods on trucks driving (for the most part) directly from picking up the load to the drop off.

- Less-than-truckload (LTL). The transportation of relatively small parcels or packages that are grouped together for pickup and delivery.

Of course, the boundary between FTL and LTL service can be blurry at times. In addition, there are other types of trucking services that don’t quite fit into this neat, binary clarification — for instance, private fleets — which are trucking fleets owned by companies whose primary business is not trucking services and that service primarily (if not exclusively) the transportation needs of the owner — or sanitation services.

But the distinction between FTL and LTL is useful in the context of industry waste, because LTL trucks are rarely either entirely full nor entirely empty, requiring a more nuanced approach to assessing the scale of waste. By contrast, for FTL service, a truck driving empty is more obviously waste.

Of the total 436.5 million metric tons of carbon emissions associated with medium- and heavy-duty freight, we estimate that about 49 percent were associated with FTL freight (both medium- and heavy-duty trucks).[1]

This estimate is based on our analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2002 Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey (VIUS) considering total mileage in each sector accounting for differences in the typical fuel economy of medium- and heavy-duty trucks, and differences in the carbon emissions associated with different types of fuel (e.g., diesel versus gasoline). The VIUS data are nearly two-decades old — the survey was discontinued after 2002 — but there have not been dramatic shifts in the industry so the data still likely approximate the current state of freight.

Together, these data suggest that full-truckload freight services are responsible for about 212 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent emissions.

Freight industry waste and potential savings

About one-third of the miles that FTL drivers run are empty. Estimates of the empty share of truckers’ total miles vary widely — in large part driven by differences in the types of service (e.g., FTL, LTL), types of trucks (e.g., heavy duty, medium duty), types of trailers (e.g., dry vans, flatbeds, refrigerated vans, tanks), and types of routes that they run. But for the most familiar type of interstate freight — heavy duty trucks running dry van or refrigerated freight — most surveys suggest that between 30 percent and 35 percent of total miles are empty.

Our analysis of carriers who run all or nearly all of their schedules through Convoy’s network confirm these estimates.[2] On average, these carriers ran about 35 percent of their estimated total miles empty during the first nine months of 2019. This means that about 76 million metric tons of CO2 are emitted each year (in recent years) while trucks are driving empty.[3]

For most independent, small and mid-sized carriers, scheduling loads is not their primary occupation: they spend much more time on the road picking up and delivering loads. They do not spend countless hours reviewing load and route options. Even those who work with a dispatcher may have only a limited view of the potential shipments available. Of course, this kind of work — constantly scanning shipment opportunities and calculating the most efficient combinations — is ideal work for computers and algorithms. Convoy’s automated reloads does exactly this: Identifying groups of shipments that fit neatly together in a compact schedule.

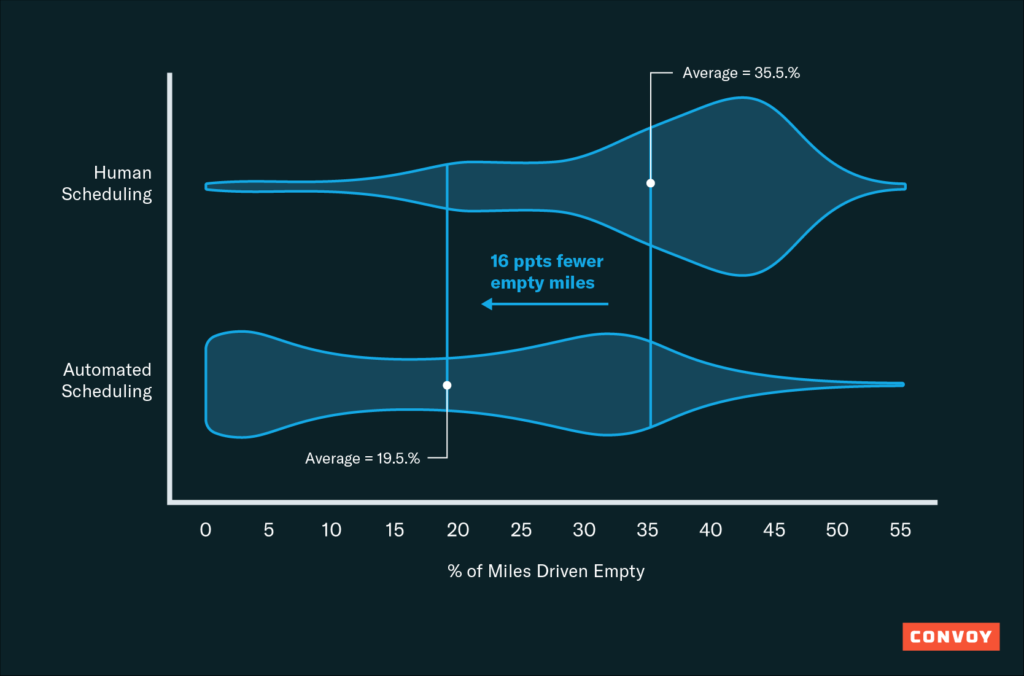

Of course, the shipments that Convoy’s platform is able to group are, in part, a function of the density of shipments we have available on our network — and that has been steadily growing. We are also constantly investing in improving our algorithms that group shipments together. With what we have been able to achieve so far, the average grouped shipment on Convoy’s platform has around 19.5 percent empty miles — a 16 percentage point, or 45 percent, reduction.

The chart below shows the distribution of estimated empty miles for carriers on Convoy’s platform who either scheduled their own routes or used a human dispatcher (labeled “human scheduling”) and grouped loads batched by Convoy’s algorithms (labeled “automated scheduling”).[4] Both groups are for loads scheduled and delivered via Convoy’s network during the first nine months of 2019.

If the FTL freight industry as a whole were able to achieve this scale of reduction in the share of miles they run empty, it would amount to carbon emissions savings on the order of 34 million metric tons. To put this saving in context, it is equivalent to approximately [5]:

- Taking 7.18 million passenger vehicles off the roads for a year — about the number of cars registered in the state of Florida.

- Planting 559 million tree seedlings and allowing them to grow for 10 years — about 2.5 the estimated number of trees in California’s Yosemite National Park or slightly more than the estimated number of trees in Washington’s Olympic National Park and Forest. [6]

- Eliminating 5.9 million homes’ use of electricity for one year — about enough to power all the homes in the city of Los Angeles for four years. [7]

- The total annual carbon emissions of the state of Oregon.

This is a conservative estimate of the potential carbon emissions savings from more efficient scheduling and route planning in the freight industry. As the number of shipments available through Convoy’s platform grows, and our ability to stitch shipments together improves, the number of empty miles associated with the typical load should fall further.

The future is now

Among efforts to create a greener future for freight, there is no single silver bullet. Supply chains and carbon accounting are both complex, multidimensional problems. This analysis is cognizant of the enormity of those challenges.

Important advances are also taking place toward improving trucks’ fuel economy: The average fuel economy of heavy-duty trucks has improved about 20 percent since the early 1980s (though even that is still less than half the improvement in fuel economy among passenger vehicles). Alternative sources of energy to power trucks — such as electric trucks — hold enormous promise, but remain in their infancy. (For long-distance heavy-duty vehicles at least; the technology and adoption is further ahead for smaller trucks and shorter-distance freight.)

Reducing the miles that trucks run empty has proven to be one of the industry’s most intractable challenges over the past few decades. That is quickly changing. The technology to reduce the number of miles trucks drive empty has arrived. At Convoy, it has been part of our mission from the very start.

Read more about Convoy’s environmental sustainability initiatives.

Thanks to Arpan Sinha and Allison Smith who contributed to this research.

[1] We assume that medium-duty trucks receive on average 8.5 miles per gallon and heavy-duty trucks receive on average 6.5 miles per gallon. In addition, we assume that diesel vehicles emit 22.4 pounds of CO2 per gallon of fuel consumed and gasoline-powered vehicles emit 19.6 pounds of CO2 per gallon, in line with estimates from the U.S. Department of Energy.

[2] We excluded carriers who delivered any loads via Convoy’s trailer drop-and-hook program, and any carriers who delivered any automated reloads.

[3] This assumes that trucks consume the same amount of fuel and emit the same amount of carbon driving full as when they drive empty, which is not necessarily the case. The extra tonnage associated with a full trailer — and even different commodities in the trailer — reduces the fuel economy of most vehicles. However, the averages are a reasonable abstraction for the industry-level analysis.

[4] For the “human scheduling” category, we exclude carriers who delivered any loads via Convoy’s trailer drop-and-hook program, and any carriers who delivered any automated reloads.

[5] Conversions between carbon emissions and other metrics from the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator.

[6] Estimates of tree coverage in primary forests range between 50,000 trees and 100,000 trees per square kilometer. We used the midpoint of this range and multiplied it by the area of each of the parks/forests.

[7] According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 American Community Survey, there were about 1.5 million residences in the city of Los Angeles, California.